Imagine if, when you start asking so much more of your Mac that you need it to be faster than it is, you could just pop the CPU out and insert a new, faster one? Today, that idea is preposterous—at least for Macs, and yes, I hear you spluttering, PC fanboys—but it was not always so.

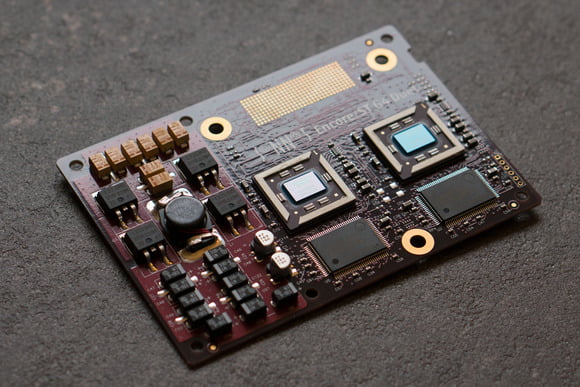

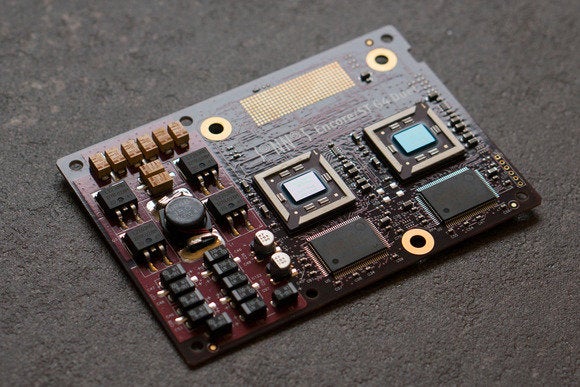

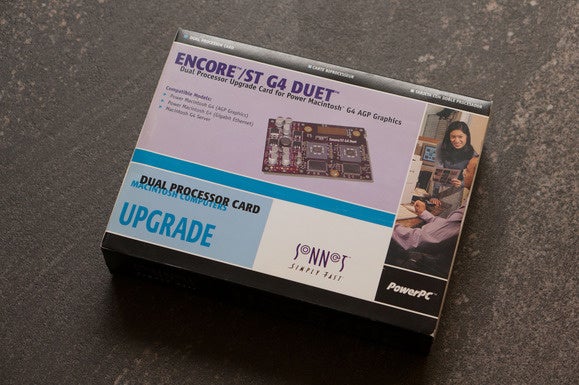

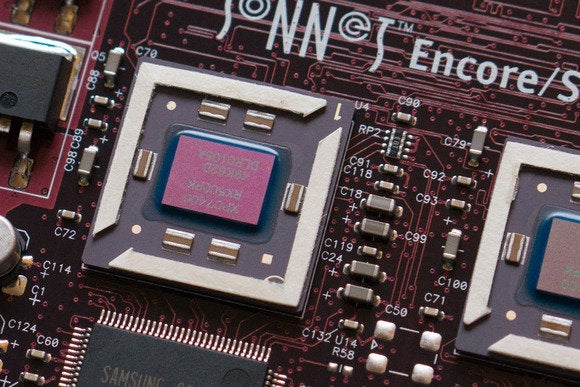

Above you see the Encore/ST Duet, a dual-processor G4 chip made by Sonnet which you could swap into a Power Mac G4 (AGP Graphics) to boost its performance. The manual blithely suggests that all you need in order to do this is a screwdriver and some pliers, singularly failing to mention that you also need confidence you could bounce a bear off, and a certain devil-may-care insouciance.

CHRISTOPHER PHIN

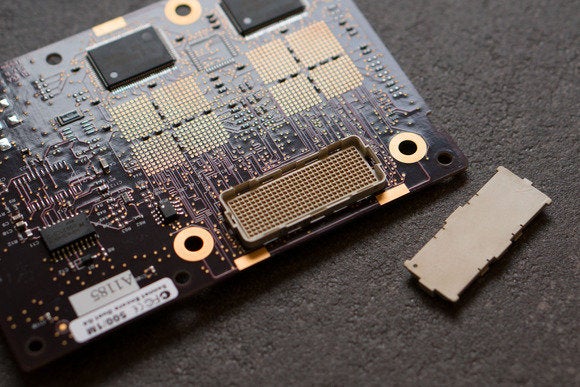

CHRISTOPHER PHINThat’s actually a little unfair. The process here really was pretty simple, involving removing the big, finned heatsink over the original CPU by releasing some retaining clips, undoing three screws, swapping the upgrade in, and reattaching the heatsink, having first sandwiched in this adapter.

CHRISTOPHER PHIN

CHRISTOPHER PHINThe whole thing connects to the rest of the G4’s motherboard through this excitingly serious-looking connector, which comes with a little plastic cover you pop off before fitting.

CHRISTOPHER PHIN

CHRISTOPHER PHINI have murky memories of doing a CPU upgrade to one of my Power Mac systems, though, as a much younger man. It involved thermal paste, swearing, and a solemn promise to any god you care to mention that I would never attempt anything like this again.

Looking through these instructions, though, it all looks not just achievable, but actively easy. That’s just as a result of experience and practice, though. I remember my dad, a teacher, asking one of his colleagues in IT if we could bring my Mac and a PCI TV tuner card I’d bought round to his house one evening so he could fit it, since I’d tried, failed, and been petrified that I would break something. In fact, I just hadn’t pushed hard enough to seat it, but until you know that, it feels like you’re pushing so hard something is bound to break.

And upgrading a CPU? Ripping out your Mac’s brain and transplanting in a new one? However easy that process looks to me in 2016, as a teenager it would have had my hands trembling with a fear that I was going to do something wrong.

And that’s entirely my problem, I know—plenty of people don’t have those hang-ups, and I envy them their equanimity. I console myself with the assumption that people like me are disproportionately drawn to Apple, where stuff works with less fiddling and tinkering at a technical level than was at least traditionally true with Windows PCs, and that there is therefore a better than average chance that you, reading this, will empathize.

CHRISTOPHER PHIN

CHRISTOPHER PHINStill, upgrading components piecemeal had obvious advantages. Apart from the lessened environmental impact compared to just buying a new Mac, it was significantly cheaper. This particular card might have cost an eye-watering thousand bucks or so when it was introduced, but contrast that with the price tag of the Macs it fitted, which started at $2,499 and climbed to $3,499—and all of those were single-CPU configurations, so this dual-CPU upgrade would make a big difference, at least for those few apps that then supported multi-cores.

CHRISTOPHER PHIN

CHRISTOPHER PHINBy this point, I know there will be plenty of people nodding along and grumbling that t’aint like that no more. The fact that Macs these days use standard Intel CPUs should mean it’s even easier to do, right? Well, I get that, I do. But I find it hard to muster up much enthusiasm for the fight, and not just because there’s as much chance of winning against Apple’s current practices as a kitten has against Lord Voldemort.

For one thing, for a few years now computers have been “fast enough,” at least in CPU terms, for lots and lots of us, so there isn’t the same need—outside of professional markets where time really is money—to be forever pushing for faster and more capable processors.

Even more importantly, though, I realize if I really think about it that by the time one of my Macs is starting to feel underpowered, everything else has moved on as well. I don’t just want a faster CPU, I want the faster interconnects for data transfer, I want the Retina screen, I want the lovely new enclosure, and so on.

It’s easy to feel nostalgic for a time when Macs were infinitely more tinkerable with than they are now—as I have proven over the previous 60 installments of Think Retro!—but maybe, just maybe, those rose-tinted glasses blind us to how the very nature of computing has changed and with it has gone the same requirement, if not the desire, for upgradeability.

One last thing. This particular card is completely unused, and was sealed until I opened it to take these pictures, but I don’t have a Mac suitable for it. If you have a Power Mac G4 AGP Graphics (one of the three-slot Sawtooth models) then leave a note telling me why you want it in the comments below; I’ll pick the most interesting story and ship it off to you!

[source :-macworld]