Lena Söderberg started out as just another Playboy centerfold. The 21-year-old Swedish model left her native Stockholm for Chicago because, as she would later say, she’d been swept up in “America fever.” In November 1972, Playboy returned her enthusiasm by featuring her under the name Lenna Sjööblom, in its signature spread. If Söderberg had followed the path of her predecessors, her image would have been briefly famous before gathering dust under the beds of teenage boys. But that particular photo of Lena would not fade into obscurity. Instead, her face would become as famous and recognizable as Mona Lisa’s—at least to everyone studying computer science.

In engineering circles, some refer to Lena as “the first lady of the internet.” Others see her as the industry’s original sin, the first step in Silicon Valley’s exclusion of women. Both views stem from an event that took place in 1973 at a University of Southern California computer lab, where a team of researchers was trying to turn physical photographs into digital bits. Their work would serve as a precursor to the JPEG, a widely used compression standard that allows large image files to be efficiently transferred between devices. The USC team needed to test their algorithms on suitable photos, and their search for the ideal test photo led them to Lena.

According to William Pratt, the lab’s co-founder, the group chose Lena’s portrait from a copy of Playboy that a student had brought into the lab. Pratt, now 80, tells me he saw nothing out of the ordinary about having a soft porn magazine in a university computer lab in 1973. “I said, ‘There are some pretty nice-looking pictures in there,’ ” he says. “And the grad students picked the one that was in the centerfold.” Lena’s spread, which featured the model wearing boots, a boa, a feathered hat, and nothing else, was attractive from a technical perspective because the photo included, according to Pratt, “lots of high-frequency detail that is difficult to code.”

Over the course of several years, Pratt’s team amassed a library of digital images; not all of them, of course, were from Playboy. The data set also included photos of a brightly colored mandrill, a rainbow of bell peppers, and several photos, all titled “Girl,” of fully clothed women. But the Lena photo was the one that researchers most frequently used. Over the next 45 years, her face and bare shoulder would serve as a benchmark for image-processing quality for the teams working on Apple Inc.’s iPhone camera, Google Images, and pretty much every other tech product having anything to do with photos. To this day, some engineers joke that if you want your image compression algorithm to make the grade, it had better perform well on Lena.

To male software developers, the story of Lena has generally been seen as an amusing historical footnote. To their female peers, it’s just alienating. “I remember thinking, What are they giggling about?” recalls Deanna Needell, now a mathematics professor at the University of California at Los Angeles. She first encountered Lena in a computer science class in college and quickly discovered that the model in the original photo was in fact fully nude. “It made me realize, Oh, I am the only woman. I am different,” Needell says. “It made gender an issue for me where it wasn’t before.”

Needell, like many other women (and some men), questioned the use of a Playboy centerfold, but they were mostly ignored. In the mid-1990s, in response to requests from readers to ban Lena from the pages of a trade journal, David Munson, the magazine’s former editor, wrote an editorial encouraging engineers to consider using other images but argued against an outright ban on the grounds that many engineers did not find the use of Lena degrading. The former president of an imaging trade group, Jeff Seideman, campaigned to keep Lena in circulation, arguing that, far from being sexist, the image memorialized one of the most important events in the history of electronic imaging. “When you use a picture like that for so long, it’s not a person anymore; it’s just pixels,” Seideman told the Atlanticin 2016, unwittingly highlighting the sexism that Needell and other critics had tried to point out.

“We didn’t even think about those things at all when we were doing this,” Pratt says. “It was not sexist.” After all, he continues, no one could have been offended because there were no women in the classroom at the time. And thus began a half-century’s worth of buck-passing in which powerful men in the tech industry defended or ignored the exclusion of women on the grounds that they were already excluded.

Today, according to a recent study published by Axios, even famously sexist Wall Street employs a higher percentage of women than tech. In both industries, only a quarter of leadership roles are occupied by women, but at the top banks half of all employees are women, compared with a third at big tech companies. Women-led startups receive a mere 2 percent of funding from venture capitalists, which isn’t much of a surprise since only 7 percent of VCs are women. At a time when a degree in computer science guarantees a six-figure job offer to any young person with a modest intellect and a willingness to live in the Bay Area, women earn just 17.5 percent of bachelor’s degrees in computer science. That percentage has remained flat for a decade.

I’ve spent the last eight years covering Silicon Valley, most recently as the anchor of Bloomberg Technology. During that time, gender disparities have always hung in the background, present but often unacknowledged. Off-camera, guests would sometimes complain about a Silicon Ceiling—a sense that women’s opportunities in the tech world are severely limited—but they rarely wanted to discuss the subject on the record. And so, two years ago, I set out to investigate the problem and, more important, try to understand what the industry can do about it. The tragedy, as I argue in my book, Brotopia, is it didn’t have to be this way. The exclusion of women from technology wasn’t inevitable. The industry, it turns out, sabotaged itself and its own pipeline of female talent.

In tech’s earliest days, programmers looked a lot different from the geeky men we now imagine when we imagine tech workers. In fact, they looked like women. One pioneer was Grace Hopper, a mathematics Ph.D. and rear admiral in the U.S. Navy, who was one of the first people to program the Mark I, a giant Harvard University computer used by scientists to model the effects of atomic bombs. After the war, Hopper invented a now-ubiquitous programmer’s tool known as a compiler, which creates a process for translating source code into a language machines can understand.

Hopper was hardly an anomaly. In 1946, six women were selected to become the first programmers of the U.S. military’s first computer. In 1962, as depicted in the 2016 film Hidden Figures, three black women working as NASA mathematicians helped calculate the flight paths that put John Glenn into orbit. A few years later, a woman, Margaret Hamilton, headed the team that wrote the code that plotted Apollo 11’s path to the moon.

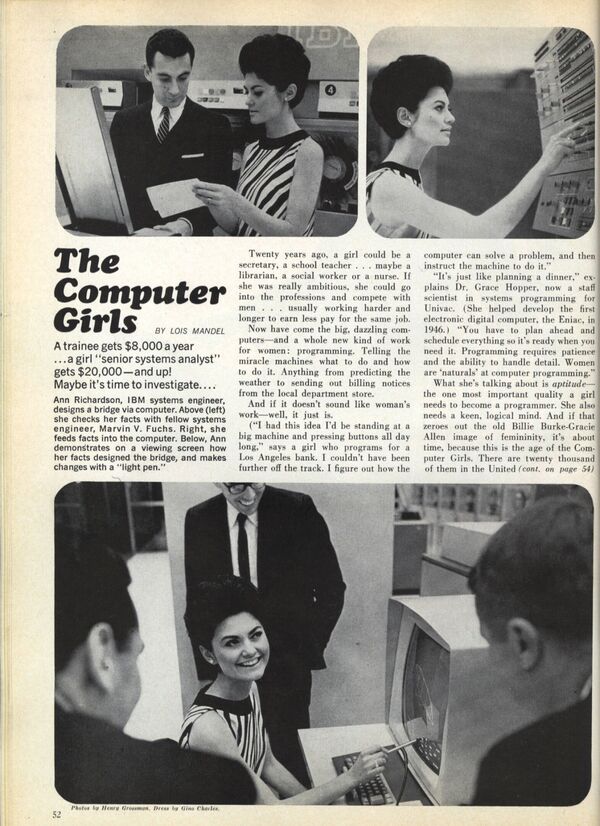

During all of this, the term “programmer” had a negative connotation, at least among men, as women’s work—similar to operating a telephone switchboard or being in a typing pool. A 1967 Cosmopolitan article, “The Computer Girls,” let it be known that “a girl ‘senior systems analyst’ gets $20,000—and up!”—equivalent to making roughly $150,000 a year today. The photo of a real-life female IBM engineer, who wore a dress, pearl earrings, and a short bouffant, appeared alongside the piece. “Women are ‘naturals’ at computer programming,” Hopper told the magazine.

But just as Cosmo was encouraging a broader selection of women to seek fat paychecks in this new field, men, also in search of highly paid jobs, started pushing women out. In the mid-1960s, System Development Corp., a pioneering software company that’s now part of the consultancy Unisys Corp., enlisted two male psychologists to scout recruits. The psychologists, William Cannon and Dallis Perry, profiled 1,378 programmers, only 186 of whom were women. They used their findings to build a “vocational interest scale” that they believed could predict “satisfaction” and therefore success in the field. Based on their survey, they concluded that people who liked solving puzzles of various sorts, from mathematical to mechanical, made for good programmers. That made sense. Their second conclusion was far more speculative.

Based on data they had gathered from the same sample of mostly male programmers, Cannon and Perry decided that happy software engineers shared one striking characteristic: They “don’t like people.” In their final report they concluded that programmers “dislike activities involving close personal interaction; they are generally more interested in things than in people.” There’s little evidence to suggest that antisocial people are more adept at math or computers. Unfortunately, there’s a wealth of evidence to suggest that if you set out to hire antisocial nerds, you’ll wind up hiring a lot more men than women.

Cannon and Perry’s research was influential at a crucial juncture in the development of the industry. In 1968, a tech recruiter said at a conference that programmers were “often egocentric, slightly neurotic,” and bordered on “limited schizophrenia,” also noting a high “incidence of beards, sandals, and other symptoms of rugged individualism or nonconformity.” Even then, the peculiarity of male programmers was well-known and celebrated; today, the term “neckbeard” is used almost affectionately. There is, of course, no equivalent term of endearment for women. In fact, the words “women” and “woman” don’t appear once in Cannon and Perry’s 82-page paper; the researchers refer to the entire group surveyed as “men.”

Cannon and Perry’s work, as well as other personality tests that seem, in retrospect, designed to favor men over women, were used in large companies for decades, helping to create the pop culture trope of the male nerd and ensuring that computers wound up in the boys’ side of the toy aisle. They influenced not just the way companies hired programmers but also who was allowed to become a programmer in the first place.

In the early 1980s, enrollment in computer science classes surged at universities across the country. At first, colleges increased class sizes and tried to retrain teachers, but when that wasn’t enough, they started restricting admissions, often at the expense of women. Because more boys entering college had already spent years tinkering with computers and playing video games in their bedrooms, they had a “superficial advantage” over girls, according to Ed Lazowska, a longtime computer science professor at the University of Washington.

In 1984, Apple released its iconic Super Bowl commercial showing a heroic young woman taking a sledgehammer to a depressing and dystopian world. It was a grand statement of resistance and freedom. Her image is accompanied by a voice-over intoning, “And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.” The creation of this mythical female heroine also coincided with an exodus of women from technology. In a sense, Apple’s vision was right: The technology industry would never be like 1984 again. That year was the high point for women earning degrees in computer science, which peaked at 37 percent. As the number of overall computer science degrees picked back up during the dot-com boom, far more men than women filled those coveted seats. The percentage of women in the field would dramatically decline for the next two and a half decades.

There have been exceptions, of course. From its earliest days, Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin sought to hire women for key positions, setting up systems designed to ensure their company did not overlook qualified female engineers because of a bias toward hiring geeky men. They were richly rewarded. Susan Wojcicki, who rented her garage to Page and Brin in 1998, would become Google’s first marketing manager. She later helped build AdWords and AdSense—two products that form the near-perfect business model that now generates most of Google’s $100 billion or so in annual revenue. She also pushed Google to acquire YouTube, now the company’s other big moneymaker.

Soon after Wojcicki joined, Page and Brin hired Marissa Mayer, a recent Stanford graduate who became the company’s first female engineer. “They grilled me for 13 hours over two or three sessions,” Mayer says of her interviews with Page and Brin. “[They] said, ‘We really want you, and we think it’s incredibly important to have women here. We want to get a strong group of women in here early.’ ” Mayer served as product manager for Google’s search page—a role that was later expanded to include all consumer web products—during the company’s explosive growth in the mid-2000s.

Another key hire: Sheryl Sandberg, the chief of staff to former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Lawrence Summers. It was Sandberg who transformed Google’s nascent self-serve ad operation into one that’s now bigger and more powerful than any ad agency in the world—before leaving Google and doing the same for Mark Zuckerberg as chief operating officer of Facebook Inc. “They were very focused,” says Sandberg of Page and Brin. “They just cared very much about hiring more female engineers. It wasn’t perfect, but no company is.”

Despite having hired and empowered some of the most accomplished women in the industry, Google hasn’t turned out to be all that different from its peers when it comes to measures of equality—which is to say, it’s not very good at all. In July 2017 the search engine disclosed that women accounted for just 31 percent of employees, 25 percent of leadership roles, and 20 percent of technical roles. That makes Google depressingly average among tech companies.

Women who work at Google are also underpaid, according to a lawsuit filed last year by the U.S. Department of Labor, which said it’s found “systemic compensation disparities” between male and female employees after reviewing the pay data of 21,000 Googlers. In September 2017 three former Google employees filed a class action accusing the company of paying women less than men for similar work while also putting them on lower-paying career paths. The lawsuit echoes a complaint I’ve heard for years from female Googlers: that the company’s efforts to bring women on board haven’t been matched with an equally concerted effort to mentor and promote women into leadership positions. Google disputes the allegations of bias. “We have extensive systems in place to ensure that we pay fairly,” said a spokeswoman after the suit was filed.

I have no doubt that Google’s leaders have been, for the most part, well-intentioned. But those intentions haven’t been enough for the company to offset the sexist undercurrents that have defined Silicon Valley for much of its history. “If I had an intuition about where we introduced problems, it’s when you really start to scale hiring,” says Bret Taylor, who joined Google in 2003 and eventually helped create Google Maps. (He later served as chief technology officer of Facebook and is now the chief product officer of Salesforce.com Inc.) He watched Google default to the standard industry recruiting methods as it struggled to keep pace with staffing demands after its 2004 initial public offering. Its recruiters went to the same university job fairs as every other tech company, posted their openings on the same websites, and subscribed to the same questionable theories about what made for a good engineer. “The growth demanded that we move with the velocity that wasn’t necessarily as thoughtful as maybe we would have liked in retrospect,” acknowledges Nancy Lee, a former Google human resources executive. “The net we were casting was not as wide as it should be.” Ultimately, Page and Brin’s attempts to find great women leaders didn’t percolate down to other managers in the organization.

“I’ve never had a female boss, and it makes me sad to even reflect on that,” says Brynn Evans, a user interface designer at Google. “I’ve worked at Google for about six years, and I just haven’t been surrounded by women who are managers. I’ve just worked with so many men, and I’ve had crappy male bosses. Crappy and rude.” It wasn’t until she arrived at Google, Evans tells me, that she realized how isolated she was as a woman in a male-dominated field.

In 2015, Page rebranded the company as Alphabet Inc., and reorganized it into a dozen independent subsidiaries, including Google. Around the same time, he hired a female CFO for Alphabet, longtime Morgan Stanley executive Ruth Porat. Page also brought in Diane Greene, co-founder of VMware Inc., to run Google’s cloud efforts. Sundar Pichai, who was promoted to the role of Google’s CEO after Page made himself CEO of Alphabet, has formed a management team that’s 40 percent female. YouTube, which Wojcicki now runs, is a division of Google under Pichai.

Even so, exactly zero of the 13 Alphabet company heads are women. To top it off, representatives from several coding education and pipeline feeder groups have told me that Google’s efforts to improve diversity appear to be more about seeking good publicity than enacting change. One noted that Facebook has been successfully poaching Google’s female engineers because of an “increasingly chauvinistic environment.”

Last year, the personality tests that helped push women out of the technology industry in the first place were given a sort of reboot by a young Google engineer named James Damore. In a memo that was first distributed among Google employees and later leaked to the press, Damore claimed that Google’s tepid diversity efforts were in fact an overreach. He argued that “biological” reasons, rather than bias, had caused men to be more likely to be hired and promoted at Google than women.

Damore’s argument hinged on the conventional wisdom that being interested in people somehow correlated with poor performance as a software engineer. Men were more likely to be antisocial than women; therefore, he intimated, men were inherently better programmers. Damore presented this as a novel observation. In fact, it was the same lazy argument advanced by Cannon and Perry 50 years earlier.

Damore was fired for violating Google’s code of conduct. Days later, he told me he didn’t regret what he’d done because he believed he was making Google (and the world) a better place. He’s now suing his former employer, alleging discrimination against conservative white men. Putting aside that calling one’s female colleagues less competent seems like an obviously fireable offense, it’s worth asking whether Damore was an outlier at Google or a symptom of a problem Silicon Valley has been unwilling to shake. Cate Huston, another former Google engineer, published a response to Damore on Medium, the online publishing platform, that argued his beliefs were more widely held than Google’s senior managers let on. “We know when we work with dudes like that,” Huston wrote. “We know when they do our code review. We know when we find their comments on our performance review. We know.”

Google has rid itself of Damore, but if it wants to help the technology industry move past its history of discrimination, it would do well to reexamine why the company succeeded in the first place. The most commonly shared narrative at Google is that its triumph came through nerdy innovation.

There is another story to tell: that Google’s success had at least as much to do with women like Wojcicki, Sandberg, and—her controversial tenure as CEO of Yahoo! notwithstanding—Mayer. Each of them brought wider skill sets to the company in its earliest days. If subsequent managers at Google understood this lesson, that might have quieted the grumbling among engineers who had a narrow idea of what characteristics made for an ideal employee. Google’s early success proved that diversity in the workplace needn’t be an act of altruism or an experiment in social engineering. It was simply a good business decision.

Adapted from Brotopia: Breaking Up the Boys’ Club of Silicon Valley by Emily Chang, to be published on Feb. 6 by Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Emily Chang.